(This is more retro-blogging of some stuff I wrote up a couple of years ago to try to explain how economists think of minimum wages in fairly simple theoretical terms. I'd say enjoy, but that might not be the first feeling that comes to mind when you read it.)

Supply and DemandIn a market in goods and services, sellers usually come in with some

price that they're willing to sell at, and buyers come in with some

price they're willing to pay. Buyers will happily pay less, and

sellers will willingly accept more, and different buyers and sellers

all probably have different prices in mind. When the sellers price

their goods and services, or the buyers post their bids, some buyers

will find things at prices they think are acceptable, and some that

are too dear; some sellers will find buyers willing to pay their

price, and others won't. When everyone who can find a deal has done

so, then the remaining buyers and sellers can either adjust their

price to find another match, or they can go home. When everyone has

done a deal or gone home, we say that the market has cleared.

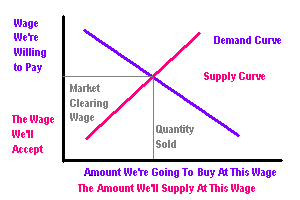

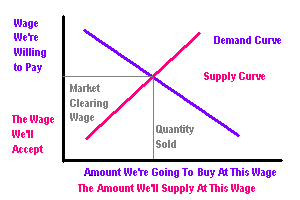

When the market is large enough for a single good or service that is

essentially identical from all providers, we call it a

commodity. In this market, there are enough sellers and enough

buyers that a single price will emerge, called the

market clearing

price, at which every willing buyer and every willing seller will

find a match. Sellers who price their product above this price will

find no takers, because the buyers can find it available elsewhere for

less. Likewise, buyers who are looking for a deal will go away empty

handed, because all the sellers can get a better price from other

buyers.

When the market gets an influx of buyers who want more stuff, or

alternatively the number of things for sale drops, the price of the

goods available will be bid up until the number of buyers willing to

pay matches the number of sellers willing to provide. If for some

reason, there are fewer buyers, or the buyers just don't want that

much of the product, or if more sellers appear with more goods, the

sellers will have to drop their prices to find buyers, since all the

buyers at the old, higher price will be gone, having already done a

deal.

Labor as a CommodityIn general, the service provided by a person as labor is not a

commodity, since each person typically brings unique skills and

productivity levels to bear on the work they perform. Considered

broadly over lots of people with similar skill and productivity

levels, a market will form the outlines of a commodity market in some

particular specialty, but this doesn't really apply to the entire

category of "Labor." One area where it comes close, however, is in the

unskilled or minimum training required labor category. On the seller

side, practically every able-bodied adult can supply this kind of

labor, and most will do so if the price is right. Some will do so even

if the price is minimal. At some price, then, the number of hours of

labor people are willing to supply will equal the quantity demanded,

and the market will clear. Once again, an influx of sellers (laborers)

or a drop in the quantity or labor demanded will tend to push the

price (wage) down, and an influx of buyers (employers) or a rise in

the quantity of labor demanded will tend to push the price up.

Markets with Price Controls

Markets with Price ControlsThe idea that there should be a minimum or maximum amount that any

particular good or service should cost or that should be made

available doesn't seem intuitively obvious to most people, but when

the service is labor, we bring some other opinions to the table.

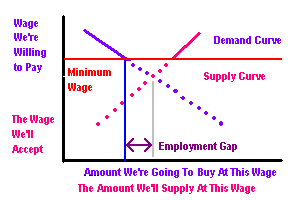

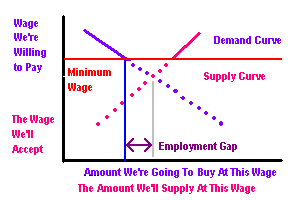

In the case of commodity labor, we call a minimum price restriction a

minimum wage. When the minimum wage is less than the market

clearing price, it has little effect. All of the sellers can find a

better deal, that is, a higher wage, and all of the buyers, or

employers, must satisfy their labor demands at the higher price or

leave their jobs unfilled. However, if the minimum wage is higher than

the market clearing price, then more people are willing to sell labor

at that price than employers are willing to buy. As shown in this

diagram, the quantity purchased will be less overall at the higher

price. The difference between this quantity and the quantity that

would be purchased at the market clearing price is the lost employment

opportunity, or the employment gap.

Note that at the higher price, sellers are willing to supply more

labor than at the market clearing price, mostly because more sellers

enter the market. The difference between the number of labor hours

made available and the number purchased is the apparent unemployment,

but this value is larger than the employment gap. One way to interpret

this is that raising the minimum wage above the market clearing price

will artificially inflate unemployment numbers, when the actual effect

on the number of people employed is smaller.

Markets with Supply ControlsThe other kind of restrictions that are commonly applied to commodity

labor markets affect supply. Any given seller has only so many hours

of labor available to sell in a week. At a high enough price, some

sellers may be willing to place every waking hour in the market. Once

again new sellers may also enter the market at the high price to sell

a few additional hours of labor.

If a restriction is placed on the number of hours any given seller may

put on the market in a week, then the quantity supplied can only be

increased by adding more suppliers to the market. Sellers lose the

opportunity to sell extra hours at the market price, but an increase

in demand for labor hours will tend to push up the price for the hours

a seller does sell by a small amount, and will bring new sellers some

employment, as the market clearing price for labor hours rises with

the increased demand.

An overtime restriction that allows the supply but increases the price

will have a combination effect. To the extent that marginal cost of

additional labor hours supplied in the labor market is low (in

commodity markets, this cost is typically negligible compared to the

cost of goods) then purchasers will tend to hire more labor from the

less expensive unrestricted market. In the labor market however,

legal, contractual, and physical limits that raise costs to employ a

marginal labor hour are common. These may include a head tax, minimum

employment hour requirements, restriction to hiring from a particular

set of suppliers such as a union, and the costs involved in training

or providing a worker with tools or supplies. These costs are the ones

that can push an employer into purchasing expensive overtime instead

of less expensive regular labor hours.

The Big Fish MarketIn a market,

pricing power comes about when one party, or group

of parties, comes to the market with the bulk of the supply or the

bulk of the demand. This is when the marginal effect of the remaining

suppliers or purchasers isn't enough to change the price of the bulk

of the goods or services sold. If a seller has pricing power, then to

an extent, that seller may charge more than the net market clearing

price, even if other sellers will sell for less, because even when the

entire amount available at a lower price is purchased, there is still

some significant demand for the remaining amount supplied at the

higher price. In this case, the market may not clear at a single

price; the supplier with pricing power may accept the risk of selling

something less than all the available stuff for sale at the set price.

Other suppliers may go along with the higher pricing and also risk not

selling all of their goods; behavior in this case is mostly determined

by what pricing will maximize profit on the net amount sold.

Similarly, when a buyer has pricing power, other buyers may be willing

to pay more, but only a few suppliers are lucky enough to sell to

them, and the remainder must sell at the lowered offering price of the

buyer with pricing power or not at all, leaving some supply that would

have sold at the net market clearing price. The buyer asserting

pricing power accepts the risk of not getting all the quantity they

wish at the price offered; pricing is generally determined to maximize

the value obtained on the amount purchased.

In a commodity market, goods in one location are interchangeable for

goods in another location; the market may state its price "FOB

Chicago" for instance, and the price between other locations for

buyers and sellers may be adjusted relative to the cost of delivering

the goods elsewhere. Commodity labor tends to be a little less mobile

as well as less interchangeable. For any given person, the cost of

supplying labor hours close to home may be small, but providing it in

the next town or city may be prohibitive.

Pricing Power in ActionLet's consider that in Potterville, adult population 1000, there may

be one employer in town with commodity labor needs, Potter's Mill,

Inc. Being the sole commodity labor buyer gives them some pricing

power relative to all of the potential suppliers of labor hours in

Potterville. Lets say someone with a lot of time on their hands did a

survey, and found all thousand potential workers in Potterville will

provide forty hours of labor a week for ten dollars an hour, but only

five hundred will for five dollars an hour; another hundred people

change their minds for each dollar an hour difference. Now let's say

the mill offers five hundred forty-hour week positions at six dollars

an hour. (Apparently no one at the mill read the survey.) Six hundred

Potterville residents apply, and one hundred are turned away. They

were willing to work, some of them for even less than six dollars an

hour, but the mill only needs so much labor, so they must look

elsewhere.

But what if the mill has six hundred positions, and is only willing to

pay five dollars an hour? Five hundred people from Potterville apply

and all are accepted, and one hundred positions go asking. Potter's

Mill Inc. can raise its offered wage, or do without that labor, but

it's up to the mill. The mill offers 100 positions at six dollars an

hour. One hundred people from Potterville take the jobs. Potter's Mill

has filled its employment needs, and saved five hundred dollars an

hour over what it would have had to pay at a market clearing price for

all six hundred positions, using its pricing power. If the mill needs

more workers, it can go back in the market and pick up another hundred

at seven dollars an hour, another hundred at eight dollars an hour,

and so on. And that's assuming some of the people over in Millerville

don't get wind of this and start applying at lower wages than the

remaining Potterville residents will accept.

Competition and Pricing PowerLet's say another business opens in town - Bailey's Pool Cleaning

Service. It's a small outfit that needs only five workers. If they

offer six dollars an hour, they may get over five hundred applicants

who currently work at the mill for less. They pick five people, and

put them to work. Them mill must fill those positions, and finds that

they must offer a higher wage to do so, but they're still the holders

of substantial pricing power, and they still save a lot of money on

labor.

If forced to compete for the Potterville pool of workers against

enough other employers, Potter's Mill would find it didn't have that

kind of pricing power, and would have to pay the higher market

clearing wage when hiring all its workers. Some workers in that market

would benefit by being paid more than they would have been willing to

work for if they had to. A few employers that would have been willing

to pay more if they needed to, find that they can save their money and

fill their labor needs for less at the market clearing price.

The Minimum Wage Comes to TownIn an effort to curb vagrancy, vandalism, and voyeurism, the town

council in Potterville decides to enact a minimum wage. Some of the

townspeople aren't being paid enough at work to keep up with the rent,

so they wander the streets at night, tagging street signs and looking

in other people's windows. To abate the scourge, they declare a

minimum wage of seven dollars an hour. Currently some six hundred five

people are employed at the town's two businesses, at wages of five or

six dollars an hour. The board of directors at Potter's Mill Inc. goes

over the numbers with management, and determines that they can't

afford to run the business with the extra sixteen hundred dollars an

hour it will cost them given their current workforce level. They

decide to relocate the mill to Millerville. Meanwhile, Bailey's Pool

Cleaning Service could have afforded to give their workers a dollar

raise, except suddenly they don't have any business as all the people

with pools in their back yard are out of work. They reluctantly close

their doors.

Leaving the extreme of Potterville behind, in a larger town with a

more competitive labor market, the effect of a higher minimum wage is

unlikely to create a ghost town. There will be some employers at the

margins whose primary cost of business is commodity labor that will be

in trouble. There will be some few people who are pushed out of the

commodity labor market, unable to command the higher wage when the

number of labor hours purchased falls off. A fair number of people

will be slightly better off, given a raise at the expense of a few

employers whose costs have gone up and whose profit margins have

fallen, or at the expense of the consumers who pay higher prices if

the costs have instead been passed along by those employers.

ConclusionOn net, when the commodity labor market is restricted, just like when

restrictions are placed in any commodity market, the total value of

the exchange possible in that market is cut. We are all worse off in

the aggregate, although for many of us there may have been no effect,

costs may have risen for very few of us, and for another few of us

there was a benefit. Sometimes in some non-economic sense, obtaining

the benefit for a few may outweigh the net negative effect on total

value. It's not easy to say that this is clearly the case for a

minimum wage.